Our Senior Curator, Elizabeth, has always said that curating is an exercise in restriction. We might have many artefacts to choose from when putting an exhibition together, but we are constrained by the physical space of the gallery, a desire not to overwhelm visitors with too many shoes, and with the goal to tell a clear and concise story. Sometimes, we are also limited by the selection of artefacts in our permanent collection. Even though the BSM has a collection of 14,000 shoes and footwear-related objects, we do have gaps when it comes to footwear from a particular time period, region or style. This was the case when we put together The Great Divide, our 18th century exhibition, so we employed three strategies to ‘fill in the gaps’ when we didn’t have the right artefacts to tell our stories.

One of the first challenges we encountered when putting together our artefact list for The Great Divide was that we are very limited in the number of men’s footwear that we have from the 18th century. Until very recently, there existed a gender bias in saving and collecting fashion. The emphasis was placed on women’s fashion, and menswear was not valued and saved. As a result, it is difficult to find many examples of men’s shoes in museums and archives.

In addition to men’s footwear, it is difficult to find examples of middling and working-class footwear. The everyday footwear for the majority of people has not been historically preserved. It is possible that these shoes were not considered special, beautiful, or of any sentimental value, and were therefore not kept over generations. It is also very likely that these shoes were completely worn through, and thrown away after use. As a result, our 18th century collection contains mostly upper-middle and upper class footwear.

There are a number of strategies that we used in our 18th century exhibition when we wanted to fill these collecting gaps, and tell stories of people whose footwear is no longer extant. Firstly, we reached out to other museums for loans. We were not able to find men’s footwear that we could borrow for the 18-month duration of the exhibit, but we reached out to the Gardiner Museum and we were able to borrow an amazing clock made for Augustus III, King of Poland, in the 1730s. This clock featured a hunting scene, including little figurines of men in their riding costumes. This was perfect as it allowed us to discuss men’s boots, and their ties to land-ownership and male privilege. Fortunately, we were able to borrow several ceramics from the Gardiner Museum, which are featured alongside our footwear throughout the exhibit.

Another strategy we used to fill gaps where we didn’t have the right artefacts was to use historic images. At the BSM, many our exhibits tend to be very image heavy because we value their ability to contextualize artefacts. Footwear in particular benefits from historic images, as shoes were never worn alone, they were worn in context of an entire outfit. The Great Divide features over 30 very carefully selected historic images, some of which help us talk about footwear styles that we don’t have on display. For example, we have a section in the gallery that talks about working class women and the second-hand shoe market. Unfortunately, we didn’t have the perfect pair of shoes to tell this story, so we used an image of a kitchen-maid to illustrate what types of footwear these women would have worn. Historic images work extremely well in conjunction with exhibit text and contemporary quotes to help us contextualize artefacts on view, or take the place of artefacts that we don’t have.

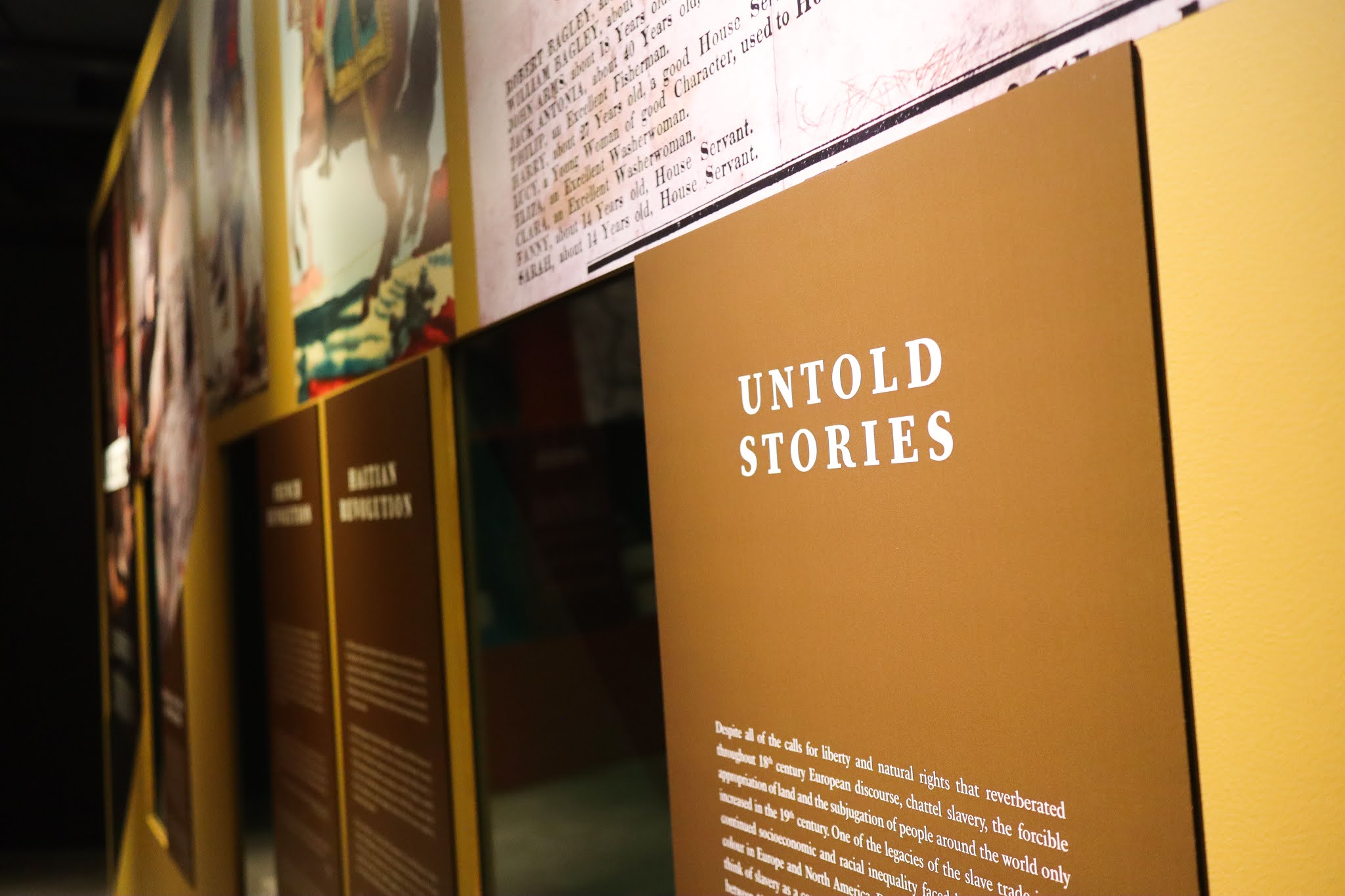

At times, the absence of certain artefacts can be used in a strategic way to tell an important story. For example, in one section of the exhibition, we have an empty showcase with text that encourages the visitor to consider whose shoes from the 18th century were not collected. This empty case is there to signal the limitations that we, as museums, have when discussing the histories of individuals and communities who were marginalized or oppressed. Often, we do not have the material culture of these communities or when we do have it, it was ‘collected’ in highly problematic ways, as museums themselves are part of the imperial project that expanded throughout the 18th century. At the same time, the empty showcase indicates that as a museum, we are having critical discussions about whose history we have collected in the past, and what artefacts we want to collect moving forward. In this way, we used the absence of artefacts to discuss the future of collecting.

In every exhibit that we do, we sometimes find ourselves wanting to discuss historic and cultural themes for which we might not have the correct footwear. By using the strategies above, we can fill in the gaps when we do not have the right artefact, and we can find clever ways to convey critical information to our visitors.

For more information about our exhibit, visit our website here.