The BSM has footwear made from a variety of materials from diverse peoples around the world. For many of the people living in coastal and riverine communities, locally caught fish is part of their diet. The skin of these fish, referred to as fish leather or fish skin textile, was sometimes used for clothing, including footwear, as it is waterproof, windproof and very strong.

These boots were made by a Nanai artist, in the early 1990s who lived on Sakhalin Island, in southeastern Russia, north of Japan. They were purchased by a curator at the Museum of Ethnology & Anthropology, St. Petersburgh and donated to the BSM in 1997.

All skins used for clothing, no matter the source creature, are tanned using a variety of methods to prevent putrefaction or rotting which is a natural deterioration until someone intervenes. The processes used, depending on the artisan, are as unique as the person preparing the skin. Some people use traditional methods, passed down over thousands of years; some have created new methods, using contemporary materials, that yield the desired result.

These boots were made in the early 1980s by Ainu artist Shigeru Kayano, who lived in Nibutani, Eastern Hokkeido, Japan. They were sewn together from 4 salmon skins.

The process starts by separating the skin from the meat, which is eaten immediately or smoked/cured for storage. Fins are usually trimmed off at this point, however, this step depends on the artist and their final intent. Next, the skin is cleaned of connective tissue and residual fats by scraping with a blunt tool; followed by tanning to preserve the skin. In some instances, urine is used to cure the skin which is then washed to stop its tanning action.

These urine tanned salmon skin boots were made in 1992 by Nunamiut artist and seamstress Eliza Chase from Bethel, Alaska. The contrasting design on the leg was created by using the other side of the skin sewn into the holes made when the fins were removed. The bottom units (soles) of the boots were made from seal skin.

Other techniques use dish detergent, fabric softener, animal brains, eggs or a combination of glycerin and alcohol. The skins are left in solution for several days, although duration can vary based on the type of tanning solution, then rinsed again. Some artisans manipulate the tanned skins until dry, others stretch them out to dry and soften them by hand just before using.

These fish skin boots with contrasting cotton legs and decorative cotton boot liners were made by Nyura Beldi in 1994. She lived in Nayhin village, Khabarovsk territory, southeastern Russian which is an area north of the Chinese border. They were purchased by a curator working at the Textile Museum of Canada and donated to the BSM.

Sometimes the fin holes were filled with a piece of fish leather sewn in place, and sometimes the edges of the holes were gathered together and sewn shut, as in the case of the boots pictured below.

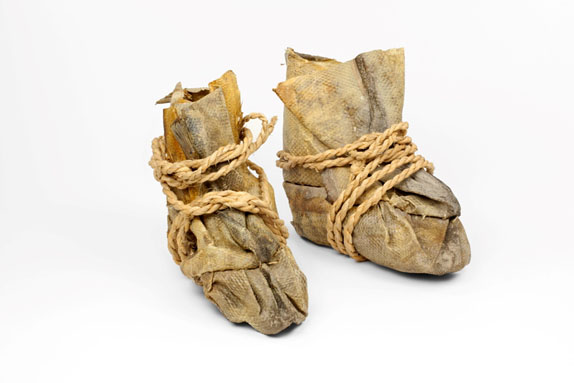

These boots were made in the 1980s by an unknown Yuit artist from Alaska.

You Wenfeng, a Hezhe artist living in China, continues the traditional techniques taught by her mother. You cleans, then dries the salmon skins. Once she has enough for her project, the skins are softened by pressing them between the ‘jaws’ of a large wooden tool carved with tooth-shaped projections.

These salmon skin boots, made by You Wengfeng in 2006, are embellished with marten fur and lined with a quilted pink cotton fabric. The curvilinear cloud designs are cut from fish skin and appliquéd in place.

Joel Isaak is an award winning Dena’ina artist and teacher based in Alaska. He uses a variety of materials, including fish skin, to create his sculptures. In 2013 he designed and made a collection of clothing, which was modeled at the Wear Art Thou fashion show. Pictured below are a pair of salmon skin pumps, a contemporary take using a material that has been part of Indigenous Alaskan culture for millennia.

Ada Hopkins

BSM Conservator