Guest Post 2012 By Samantha Conover

In my last blog I discussed the surprising prevalence of plastics within the Bata Shoe Museum. Today I would like to talk about why it’s important to identify and care for plastics. Plastics are often misconstrued as indestructible. In fact, plastics can degrade spectacularly, sometimes causing damage to materials nearby. This degradation can be unpredictable because of differing makeups in plastic composition (such as additives used in manufacture) and exposure to light, heat and moisture prior to museum storage.

Like most other materials, plastics are vulnerable to environmental weathering. Exposure to light, heat, oxygen and water can cause chemical reactions which alter the arrangement and type of chemical bonds present in a plastic. So when plastics break down visibly, they are also breaking down on a molecular level. The breakdown of a plastic can reveal itself in many ways including crumbling, cracking, stickiness, stiffness, yellowing, blooming and sweating. Because the chemical makeup of a plastic will determine how a plastic breaks down, each type of plastic tends to degrade in its own particular ways. This is why it is so important to identify plastics, as it allows conservators to strategize ways to prevent this degradation.

Rubber is most susceptible to damage caused by exposure to oxygen. Exposure to oxygen can cause crosslinking, a process that creates links between linear polymer chains. Rubber is often crosslinked intentionally in order to add strength and stability to the material. But when crosslinking happens unintentionally it can lead to brittleness. Exposure to oxygen can also cause chain scission. This is when the long polymer chains of a plastic break off to form shorter chains. Chain scission can cause cracking and crumbling or softening and oozing. Below are some images of shoes who have suffered due to oxidation.

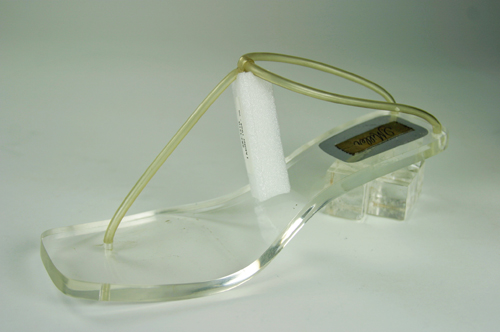

The rubber sole of this shoe has become soft and sticky. This is likely due to chain scission. In order to prevent it from adhering to other surfaces, the conservator has attached a Mylar barrier. Exposure to UV radiation and light can cause the development of chromophoric groups. This development causes a formerly white or transparent plastic to become yellow. This is very common with objects made of nylon and PVC. Below are images of shoes with nylon and PVC straps that used to be transparent, but turned opaque and yellow due to light exposure.

Yellowed nylon (above) and PVC straps (below).I’ve photographed the nylon besides a roll of new nylon monofilament to show how yellowed the straps have become with age.

Another factor involved in plastics deterioration is the use of additives in manufacture. These additives are incorporated in the polymer matrix to change physical and chemical characteristics such as colour, strength and flexibility. As plastics age, the additives can become incompatible. When this happens, the additives will separate from the plastic and leech out. For example, flexible PVC is made by adding a plasticizer during manufacture. As PVC ages, the plasticizer escapes to the surface to form droplets or a sticky film. The vinyl strap of the shoe below is covered in small dots, which are likely dried droplets of plasticizer.

Some plastics are more problematic than others. Most plastics only damage themselves as they degrade. So-called “malignant plastics” are a danger in the museum as they can harm nearby materials as they deteriorate.[1]Plasticized PVC, polyurethane, cellulose acetate, cellulose nitrate and rubber (usually highly vulcanized hard rubber) are the bad guys of the plastics world. Cellulose nitrate is the most notorious of these villains. With exposure to moisture, cellulose nitrate eventually breaks down and releases nitric oxides, which quickly become nitric acid. Nitric acid is highly corrosive, and can damage nearby objects and materials. The 1920s shoe below is decorated with two types of beads. The small beads are brass, the larger beads are of an unknown material. The brass beads that are in contact with the unknown beads are starting to corrode. I suspect that the unknown beads may be cellulose nitrate!

Most modern plastics are designed to withstand environmental pressures and remain in good condition throughout their “service lifetime.” However, this period of regular use will always be much shorter than the time an artifact is expected to remain viable in a museum. The best way to deal with deterioration is to try to stop it before it starts. Since different plastic types have different degradation paths, identifying what kind of plastic was used to create an object or part is crucial. In my next blog I hope to discuss some methods of identification and to solve plastic mysteries. Plastics conservation is a relatively youthful field and much of the work being done right now is groundbreaking research. If you want to learn more, I suggest you check out the work of the POPART project at http://popart.mnhn.fr/

[1] I prefer to the phrase “bad neighbors” a term coined by John Morgan of the Plastics Historical Society. I think “malignant” sounds a little too harsh. These plastics may do wrong, but they know not what they do… it’s not their fault!